Essay question //

What are the effects of late capitalism pertaining to consumer culture that Sara Cwynar verbally and visually communicates in her film Rose Gold and to what extent does this correspond to Sianne Ngai’s theoretical aestheticisation of commodified cuteness?

Introduction_

In this text, I will examine particular frames and interpret specific excerpts of monologue from Sara Cwynar’s 2017 film titled Rose Gold in order to assert Sianne Ngai’s theorisations of the aesthetic judgement of the cute as the dominant aesthetic of consumer society today. I will discuss how Cwynar’s visual and vocal cues in this filmic art work express the effects of late capitalism in consumerist society; specifically addressing the invention of the colour rose gold, in conjunction with Ngai’s concepts of commodified cuteness. I will refer to Adam Jasper’s email interview with Ngai for Cabinet Magazine. I will also discuss The Cuteness of the Avant-garde, a chapter in Our Aesthetic Categories, which makes Ngai’s argument for the cute clear along with the zany and the interesting; ‘these aesthetic categories, for their marginality to aesthetic theory and to genealogies of postmodernism, are the ones in our current repertoire best suited for grasping how aesthetic experience has been transformed by the hypercommodified, information-saturated, performance-driven conditions of late capitalism.’ In this text, I focus on the way in which hypercommodification is materialised in Ngai’s text. And how Cwynar, through the visual formality of the film, proposes that hyperconsumption has become a social normality. I will be comparing Ngai’s theorisations of the cute to the way in which the objects in the film Rose Gold, especially the essence of the colour rose gold, are consumed because they adhere to Ngai’s cute commodity aesthetic.

One_

Rose Gold 2017 is a 16mm film transferred onto video by Canadian visual artist, Sara Cwynar. Born in 1985, she is currently represented by Cooper Cole, Toronto and the Approach Gallery in London.

Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar. 2017. 16mm film transferred to video. Gallery view. Image courtesy of the artist.

A magenta pink typeset that reads ‘Rose Gold’ flashes onto the screen against a jet black background. It lingers for just a little while longer than a subliminal message would. Followed by a sharp intake of breath indicating that a woman is about to speak. She’s quickly interrupted by a male voice who addresses the viewer as if in conversation with friends. “They invented this new colour, rose gold, and I’m mesmerised. A new object of desire. I totally fell for it.” Immediately, the viewer is introduced to the idea of a new object, in this case it is a new colour. The feeling that this produces in the narrator is palpable. He is vocalising his desire, and insinuates that he has acted upon this desire, or at least understood that the invention of rose gold has had an effect on him. According to Ngai, something that is cute has a surprising power and so, anything that can be objectively defined as cute seems to have become so paradoxically central to late capitalist culture. There is an element of surprise, and a sense of acceptance to the colour rose gold in the man’s voice. It’s as if he is trying to persuade the viewer that rose gold is a real and valuable thing. He wants everyone to understand rose gold as universally ‘mesmerising’. Ngai states that the cute is a good example of a contemporary aesthetic category that makes a claim for universality. She goes on to say, ‘I’m compelled to speak of it (the cute) as an objective property of an object, which reflects my demand that everyone judge that object the same way.’ Rose gold can be objectively defined as a cute commodity because it is a mixture between pink, a soft and feminine colour, and gold which implies that something is highly valuable. The title of the film is efficient in expressing commodified cuteness in a late capitalist society because rose gold is an overtly feminine colour that can be applied in the production of any new item and therefore become an object of desire. With this said, in the 8 minute film the viewer is not subjected to a lot of objects that actually are rose gold. Moreover, the film is concerned with showcasing a seamless transition with which literal objects become abstract concepts; ‘Rose gold doesn’t need to be anything at all.’ Value and desire merge and “Since consumption is the activity in which one realises a commodity’s use value” the viewer is bombarded (in order to consume as much as possible) with numerous objects of desire, with varying objective use value. Cwynars’ Rose Gold highlights the simultaneous fading and failure, and the often futile fates of objects we want to buy or have bought. A certain trash vs. treasure trickery mindset that has shaped consumer culture today is materialised throughout the film, the viewer is then left to consider the flux of value when fantasising about objects they want to own. ‘Cuteness is also a commodity aesthetic, with close ties to the pleasures of domesticity and easy consumption.’ In the film the male narrator states “There was a time when we were able to draw up an encyclopaedia, an exhaustive catalogue of all the objects in the world.” This time, or past world that the male voice is referring to is certainly over for physical objects on planet Earth have far surpassed a measurable number. Hence the term hypercommodification. The narration continues “Since then everyday objects proliferate.” At this stage in the film the monologue becomes immediately indecipherable as multiple voices begin to overlap one another in a jumbled manner. It’s as if the viewer is forced into a space containing lots of objects that begin to communicate with them against the viewer’s will. I will liken this to advertising strategies; a prolific and somewhat undetectable symptom of late capitalist society. In the next moment of the film, Cwynar embarks on the visual proliferation of tangible items which begin to appear on the screen faster and faster and in larger numbers. This montage serves as a visual analogy for today’s world as a consumerist society, potent with advertisement. Similarly to the way in which Ngai explains the cute to proliferate as a commodity of ‘continuousness and everydayness of our aesthetic relation to the often artfully designed, packaged and advertised merchandise that surrounds us in our homes, our workplaces and on the street.’ Cwynar’s visual and vocal methods of working in this film seduces the viewer to revalue objects through a somewhat sentimental lens. The film evokes feelings of nostalgic lust for past objects of desire as they are mixed with new ones. For example, analogue clocks are offered up in the same way that iPhones are, and a plethora of colourful melamine kitchenware succeeds the golden gates of Gucci.

A commodity by definition, is something that is of use or of value to an individual. Ngai understands that ‘cuteness, for its part (in the ideology of aesthetic categories), is by no means an unequivocal celebration of the commodity form.’

The way in which Cwynar presents the aesthetic catagorisation of objects belonging to the commodification of the cute is fast paced, organised, and done in colourful modus. This illustrates the very nature of consumerism. When one is presented with a new object, especially if said object is objectively cute, one is coaxed into seeing this seemingly valueless item under a veil of desire which is “Indeed, what these aesthetic categories based on milder or equivocal feelings make explicit.”

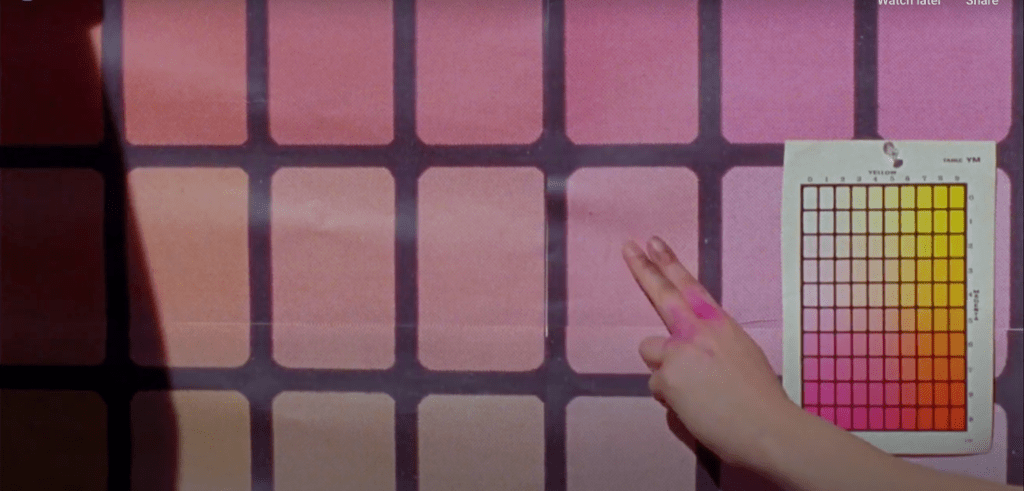

Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar. 2017. 16mm film transferred to video. (1m19s)

The ongoing and often overlapping narrative in Rose Gold draws particular attention to how Ngai characterises the cute as an objective aesthetic experience that can become overpowered by a second feeling of manipulation or exploitation. In the next moment of the film the male narrator asks himself and the viewer solemnly, “What is a good life, when something you desire is actually an obstacle to your fruition.” It’s important to note that much of the intellectual content in the film Rose Gold is delivered in an audibly convoluted manner, words overlap and sentences lose their clarity. But in this excerpt of monologue, Ngai’s proposal becomes legible in the context of consumerism and also corresponds to what the narrator is expressing. The second feeling of manipulation or exploitation can be understood as guilt or regret with regards to a purchase, when one realises that they have been tricked into buying something they don’t necessarily need. But because they liked the look of it they ‘totally fell for it’. And so, to consume is to be persuaded by the feelings of desire that an object arouses. Ngai proposes that there are states of weakness in ‘minor’ or non-cathartic feelings that index situations of suspended agency. She is talking here about objects that conform to the contemporary aesthetic category of the cute. Arguably, something cute, in this case the colour rose gold, induces desire. This leads to the moment of weakness in the consumer not the consumable. The moment of weakness is the desire to purchase said cute object. And so desire is a cathartic feeling because it produces a human response. The male narrator vocalises that he ‘totally fell’ for the object, this indicates submission on his part to the colour rose gold. Thus, the weak spot in non-cathartic feelings that index situations of suspended agency are something that objectively cute objects can produce in the consumer resulting in the act of submission to it. In this context to submit is to purchase, or at the very least the desire to purchase. Ngai believes that ‘Our desire for the cute commodity mirrors the desire it appears to have for us, a mimesis repeated in the compulsion to imitate the “soft” properties of the object in our speech. Conflating desire with identification, or “wanting to have” or “wanting to be like”’ The monologue in the film continues to be distorted and difficult to follow in the next moment of the film, as the male and female voices overlap whilst saying different things. However, “Every possession is an extension of myself.” becomes decipherable amongst the vocal jumble. This excerpt confirms Ngai’s ideas about the small disparity between the consumer and the commodity. Something will be bought if the consumer sees similarities in the item they are buying and themselves. I believe this negates Ngai’s proposal that the cute generates non-cathartic feelings; she explains these as ‘feelings that do not facilitate action, that do not lead to or culminate in some kind of purgation or release.’ I would say in the film rose gold, that this feeling of release is the act of accumulation by buying into a colour. Purchasing something that is rose gold simply because it is a new commodification of cuteness. In the next moment of the film the male narrator tries to rationalise how he could have possibly ‘fallen for’ rose gold. He explains to the viewer that “the name of a colour is a result of a segmenting between other colours.”

Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar. 2017. 16mm film transferred to video. (0m50s)

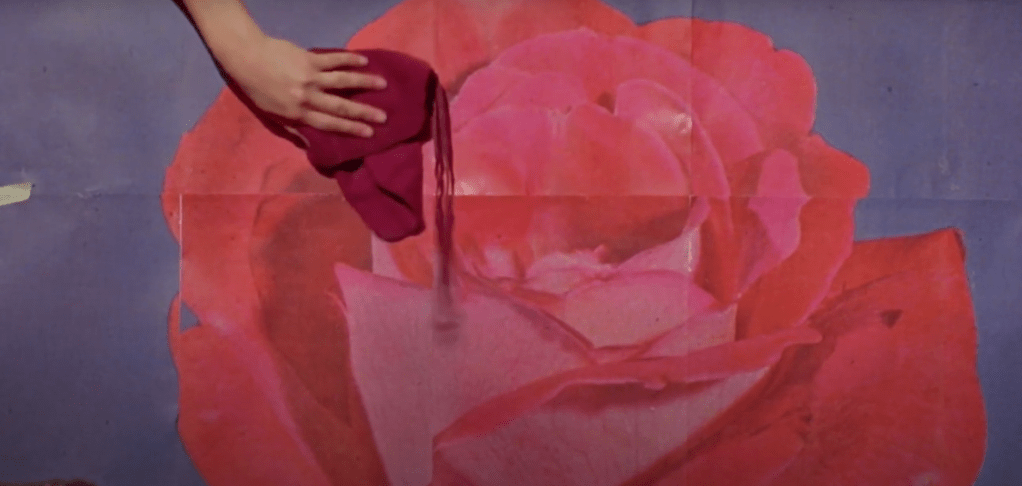

Be that as it may, it appears that he is attempting to talk himself out of consuming a cute commodity. Possibly because he now begins to assimilate rose gold with the feminine. Arguably, the masculine is programmed to protect the feminine, ‘Since cute things evoke a desire in us not just to lovingly molest but also aggressively protect them’ Here, Rose Gold approaches the topic of gender based discrimination which cuteness as an aesthetic oriented toward commodities does. By interweaving copious amounts of cute and feminine imagery; harnessing the connotations and determinative judgements of colour, through the guise of consumerism, the sentimentality of desire becomes warped yet the retro essence of the film reflects what cuteness stands for. I believe Ngai’s understanding that ‘cuteness is an aesthetic much more evidently rooted in material commercial culture than in the language arts.’ becomes relevant at this point in the film. Another significant moment in the film associates hypercommodification with the fleeting feeling of desire, which can only be an everlasting feeling if it can continue to materialise physically, through the constant production and consumption of objects. Similarly to how Cwynar has been snubbed as merely ‘having a moment’ as an artist, at 1m:48s the male voice speaks assertively but with sadness in his voice, “Several male artists that I know have told me that I’m having a moment.” Cwynar finishes off the sentence that he was saying on her behalf, “As if the moment will pass soon.” The male artists addressing Cwynar are insinuating that her moment as a popular artist is fleeting, reminding her of her place below men in society and in the art world. This aligns with Ngai’s comments that, ‘Cuteness is a way of aestheticising powerlessness.’ Because the cute is inextricably linked to the feminine. It is apparent that Cwynar is self aware as she likens her success as an artist to the rose gold just having a moment. The ironic nature of this sexist rhetoric coincides with Ngai’s understanding that there is an equilibrium between the cute consumer and the cute commodity, the female and the feminine. Similarly to the powerlessness of a cute object, Cwynar as a female artist is aestheticised as having little or non-lasting power because It (she) hinges on a sentimental attitude toward the diminutive and/or weak. Because she is female, therefore the weaker sex. Cwynar at this point begins to rub a pair of girlish underwear over a large scale poster of a rose, she is literally rubbing femininity in the face of femininity.

Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar. 2017. 16mm film transferred to video. (1m46s)

Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar. 2017. 16mm film transferred to video. (1m49s)

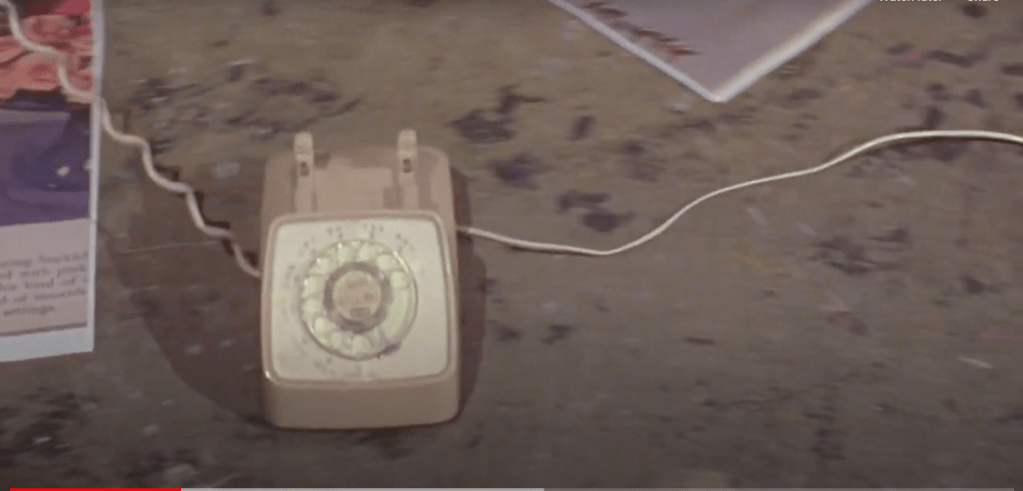

I will make fragility my last point connecting the film’s visual and verbal messages and Ngai’s theorisation of commodified cuteness. The viewer watches cracked iPhones and brand new rose gold iPhone advertisements appear as intermittent imagery amongst the seemingly robust, cumbersome landlines that move on screen.

Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar. 2017. 16mm film transferred to video. (1m52s)

Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar. 2017. 16mm film transferred to video. (1m21s)

It is imperative to note the formal qualities of the iPhone in Rose Gold when considering how Ngai compares cute objects to beautiful objects, ‘And while the anti-sentimental avant-garde is conventionally imagined as hard at cutting edge, cute objects have no edge to speak of, being simple or formally non-complex and deeply associated with the infantile, the feminine, and the unthreatening.’

Rose Gold, Sara Cwynar. 2017. 16mm film transferred to video. (0m49s)

The cracked iPhone is, by design, formally non-complex. With rounded corners, smooth surfaces and small buttons. The insinuated desire to own an iPhone complies with Ngai’s explanation of “Revolving around the desire for an ever more intimate, evermore sensuous relation to objects…” Because the rose gold iPhone is something that you touch, swipe, protect and see yourself in, it contains all of the elements that the cute commodity aestheticises. The iPhone, when presented in the film with cracks and small sections missing does appear helpless. It bears the very physical appearance of distress which corresponds to Ngai’s understanding that ‘objects seem most cute when they seem sleepy, infirm or disabled.’ The recurring visuals of the iPhone being dropped and damaged concur with ‘The desire to fondle and squeeze the object that cuteness similarly elicits – even to the point of crushing or damaging that object – might thus be read as an effort to “grasp” the commodity as a product of concrete human labor.’ I propose that when Cwynar says “one gesture away from losing all access to sustaining the fantasies I need”, she is implying that this ‘one gesture’ is the act of dropping the iPhone. The release of grip from the object, causing it to break forever, closes the gateway to further purchases (since you can shop online on your iPhone) and therefore she cannot sustain the fantasies she needs. The act of dropping the iPhone has dematerialised its own use value as a commodity that gives access to further commodities, for there is now an irresolvable split between the commodities phenomenon and fungibility. Cwynars fantasy of owning and disowning the iPhone by breaking it aligns with Ngai’s summary that “cuteness activates both our empathy and our aversion.”

To conclude, cuteness presents itself in Rose Gold as an abstract idea that dictates consumer culture. It appears to be an omnipresent force that generates a certain urgency to acquire new things and therefore the cute presents itself as a powerful aesthetic feeling. Cwynar visually and vocally corresponds to Ngai’s theorisations of commodified cuteness in her film Rose Gold because the cute is a descriptive aesthetic judgement that appears in ‘vivid contrast to beauty’s continuing associations with fairness, symmetry and proportion, the experience of cute depends entirely on the subject’s affective response to an imbalance of power between herself and the object.’