I drop my pin onto The White Cube in Mason’s yard, dubiously following the map’s dulcet tones through my headphones. After convincing myself that I know where I’m going, I ignore the directions I asked for. After a few wrong turns I find myself at the David Gill Gallery. A momentary lapse in my determination meant that I almost went in. Fueled by faint frustration at my apparent inability to find the art space that undoubtedly looks like what it says on the tin. I remind myself that it was David Altmejd that I came to see. Aboutface, I avoid the diversion I made in my own head and sheepishly reload my robot assistant and retrocede down a cobbled side alley. The White Cube erupts from the tectonics of this cul-de-sac. It’s a clearing in this urban forest, the sylvan spot of SW1. The liminality of The White Cube’s location offers an alternative to the sparse labyrinth of gothic gallery fronts. Distancing itself with a sense of individuality from the garish offerings of ye olde tyme art. It’s refreshing to see modern architecture neatly tucked away on a backstreet. Without hesitation I slid through the cumbersome glass doors and into the cube.

Gliding onto the ground floor, in an atmospherically lit space, we encounter the first of many creatures. The Vector is a sentient presence that enchants the room. Having transcended from the outside space, the hare/human splice awaits our arrival. Plinthed on a low white cuboid, The Vector rests in a meditative pose. Contemplating the burrowed hole of its very matter sinking deeper before it. The last remaining feature to be scooped out is its hand, the tool for its creation. Its anatomical shovel, a tactile trowel. The incomplete extremity lays limp over the hare’s crossed legs. Seemingly self made, we see that The Vector has been constructed with a sense of urgency.

David Altmejd, The Vector, 2022, White Cube, Expanding foam, epoxy, acrylic paint, resin, glass eyes, coloured pencil, pencil, fibreglass, glass rhinestone & wood, 397 × 182 × 182cm, Theo Christelis

It sits, gracefully suspended in the sweet spot found between inspiration and imagination. We see the very moment that follows a sense of enlightenment lapsed in time. An ethereal energy radiating from its vast amethyst ears, crystallising this creature of dreams.

David Altmejd, The Vector, 2022, White Cube, Expanding foam, epoxy, acrylic paint, resin, glass eyes, coloured pencil, pencil, fibreglass, glass rhinestone & wood, 397 × 182 × 182cm, Theo Christelis

Moments of frustration are certainly visible in the hares moulded torso. Its upper chest bears the scars of deeper excavations, the distressing pries that have concaved the malleable material. As if it had been clutched so tightly by someone who eventually had to let go. The Vector’s towering ears signal skyward like semaphore flags. Swooping our attention up to the limits of the room. In physics, a vector refers to a quantity of two individual properties; magnitude and direction. It describes the movement from one point to another. A journey of exploration, an intuitive reaction. A phenomenon that can not be expressed as a singular element. And so it is hard to determine what or to whom The Vector is signalling. A crux of ocular communication is shared, as you stare into its uncanny glass eyes. We see an unascertained sense of wisdom that guides us down the rabbit hole.

The trickster is a personality type that can be defined by playful shapeshifting and a capricious vitality. Often depicted as a mischievous beast, like the hare. Now, Altmejd unveils it as the presiding spirit of the show as we see them proliferate in the White Cube. According to Carl Jung, a psychologist of the early 20th century, the Trickster represents balance between the chaotic and the logical. Within the realms of modern psychology, the liminal space between these two contrasting vectors allow for optimised mental health. For Altmejd, our ancestral memories relate to the unconscious. Much like how our individual creation stories are inextricably linked to the people who made us; our parents. Our very existence could be likened to the point at which magnetism and direction form the phenomenon that is a vector.

On the lower ground floor, Altmejd dutifully presents us with a sculptural colony for his first show with White Cube in London. In the gallery walkthrough video accompanying the exhibition, Altmejd alludes to a sense of surrender. A point in his creative process where the work becomes intelligent enough to make its own choices. “I feel like the object has made itself and I just helped it make itself.”1 We could liken this to the coming of age tale as old as time. The question is from which perspective do we see the artwork ensuing? Childhood or adulthood? Two distinct stages in life become ambiguous as you descend into the sculpture court festering beneath The Vector. Altmejd’s show is an invitation to be playful with this balance. He makes it clear in this confusion that an ever changing combination of elements define our personality. As you weave amongst the plinthed busts, Altmejd’s creations ooze some sort of unknown familiarity. A resemblance of the artist’s anthropomorphised personality. Human features morph seamlessly into cartoon-like characteristics of the hare. When we look at the sculptures the ambivalence of naivety and wisdom is palpable. Glaring through us like refracted light. It’s blinding, as we come face to face with each individual bust. Some appear to be cross-sectioned cliff edges, weathered and eroded over time. Layers of colour and texture tear through each other revealing scribblings not too dissimilar to what you’d find magnetised onto the family fridge. On closer inspection the doodles look like crude diagrams of bodily organs. Bulbous intestines drawn with crayons create passageways through the sculpture’s surfaces. “One way in which sculpture can function like a body is to suggest that the body contains infinite space.”2 It is true that the human mind is not finite like the space around it.

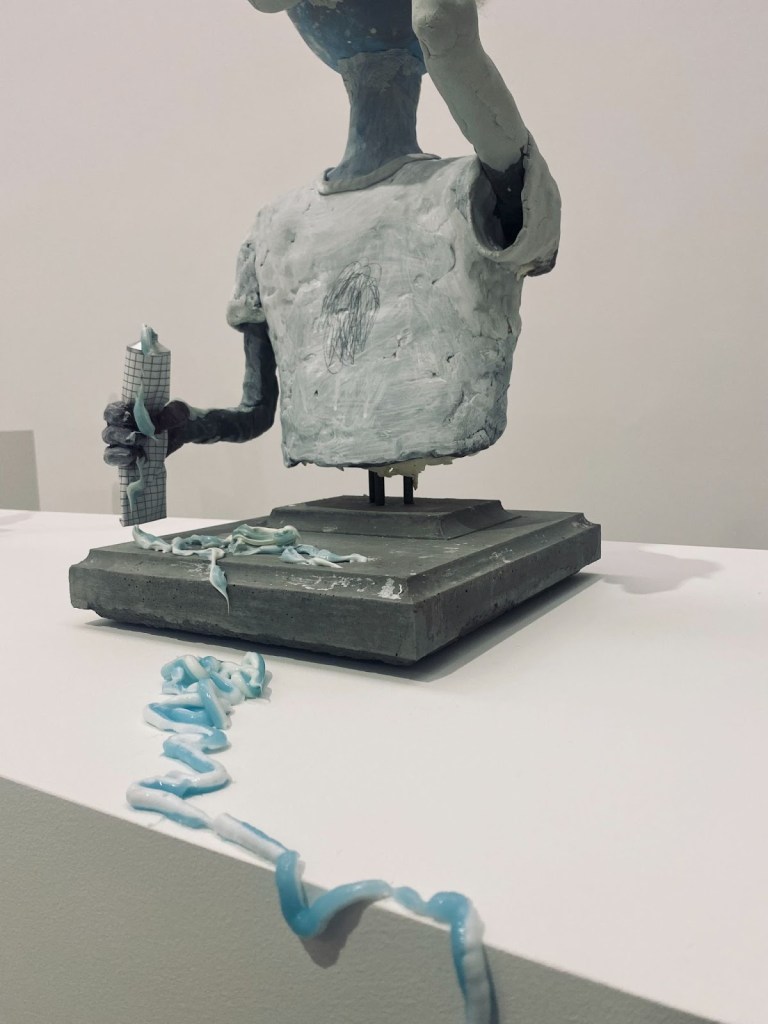

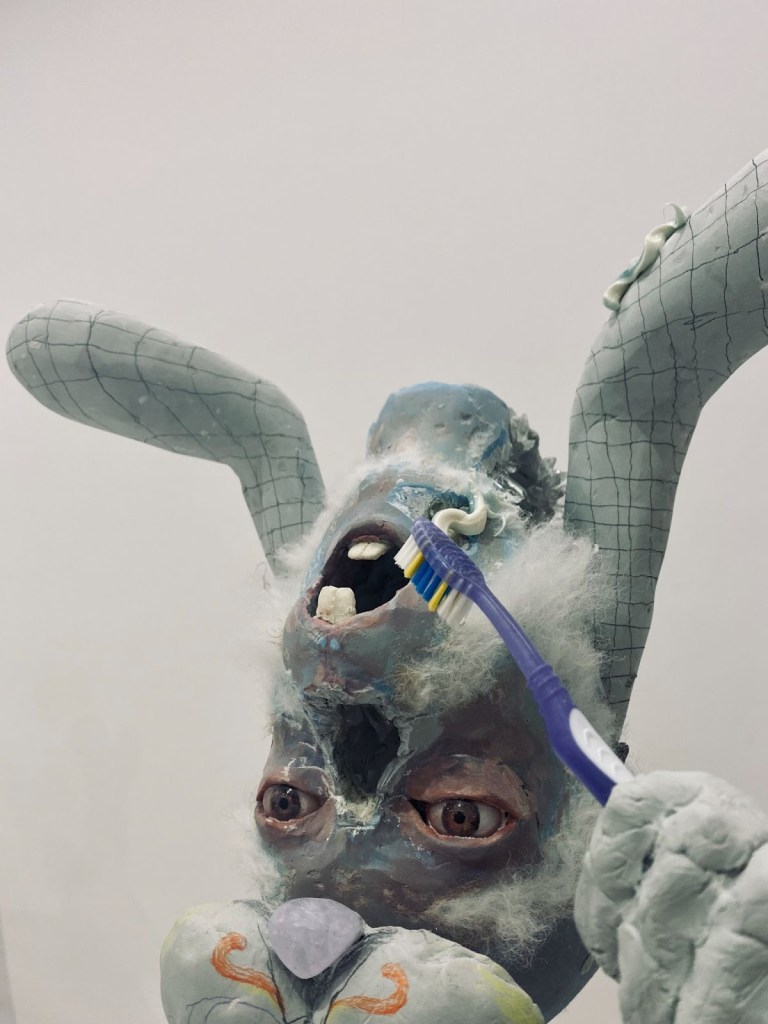

Some of the sculpture’s surfaces look like a geographical graph. Or a map of knowledge. Dense lines indicate high points and other markings create alternative terrains. Throughout the space we continue to see Altmejd’s nod to the trickster mentality. Toothpaste has been squeezed erratically over the plinths and onto the gallery walls. It seems we know who the culprit is. ‘Glitch’ grips a tube of the stuff in one hand and in the other, he thrusts a toothbrush toward its rodent buck teeth.

David Altmejd, Glitch, 2022, White Cube, Expanding foam, epoxy, acrylic paint, quartz, poodle hair, toothbrush, aluminium tube, coloured pencil, pencil, glass rhinestones, concrete, steel & wood, 83 × 37.1 × 33.7 cm

David Altmejd, Glitch, 2022

White Cube, Expanding foam, epoxy, acrylic paint, quartz, poodle hair, toothbrush, aluminium tube, coloured pencil, pencil, glass rhinestones, concrete, steel & wood, 83 × 37.1 × 33.7 cm

Sketched with juvenile vigour, infant graffiti can be found at half height on the plinths and walls. It’s as if we are being asked to read and understand the language of someone who has not yet learnt the alphabet. Some aspects of the work are far more menacing. The morbid manifestations make for uncomfortable viewing. The pieces that appear flesh-like have a disturbing viscerality to them. We are asked to deal with emotions that we did not know sculpture could unearth. Dull melancholy takes hold as you look searchingly over the surface of The Mother. Her translucent sinew is tenderised and tortured. She is not lifeless, but connections to her prefrontal cortex appear severed. Her presence in the room dissolved. As if mundane repetition has left her subdued and semi conscious. What looks like a dried pomegranate is sliced open and set into The Mother’s skull. It is difficult to determine whether Altmejd is replicating the appearance of the brain or if he is insinuating that the shrivelled fruit is in fact a Rorschach inkblot test. These psychological tests of symmetry arouse complex perceptions in the subjects mind in order to analyse and examine personality traits or defects.

David Altmejd, The Mother, 2022

White Cube, Expanding foam, epoxy, acrylic paint, resin, concrete, pencil, crayon, Sharpie, glass eyes, steel & wood,

79 × 37.5 × 41 cm

David Altmejd, The Mother, 2022

White Cube, Expanding foam, epoxy, acrylic paint, resin, concrete, pencil, crayon, Sharpie, glass eyes, steel & wood

79 × 37.5 × 41 cm

Alas, we remember that an overly intellectual approach to life’s problems can be carried into excess.3 Facts and information can serve the fateful collapse of imagination. Its swings and roundabouts in here. We retrace our steps, taking another lap around the mock sculpture court. Trying to figure out how we got here. Is Altmejd’s work going in circles? Or is he leading us through them? We encounter rabbit holes in the very walls of the exhibition space. We are drawn to them and in return we find offerings of rabbit droppings, again alluding to the mischievous nature of the trickster.

We can now see a correlation between The Vector’s amethyst-like ears and the actual quartz crystals we discover wedged into many of the busts and heads on the lower ground. “Contrast itself generates energy.”4 Could this be Altmejd’s way of exploring the self correcting forces of our cultural hero, the Trickster? The crystals work as an energy flow through the sculptures. They breathe life into the object, no longer ossified and powerless. The holes in the sculptures create entry and exit points, leading us to a space outside of the conscious mind. We distinguish the sculptures’ duality. Some of the works share the same pair of eyes, yet the doubling effect encourages us to perceive them as separate beings. They are a yin and yang representation of what can be observed visually and perceived mentally. It is the multi-faceted portraiture that stresses the unity of the mind.

The whole show encapsulates infinite jest, wrapped up in the paradox of a lobotomised brain child. Altmejd asks us to be realistic, while demanding the impossible. To see the world through the trickster’s eyes.

Speculum mentis est facies et taciti oculi cordis fatentur arcana. – “The face is the mirror of the mind and the eyes silently confess the secrets of the heart.” – Jerome

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kL_miBZmiy4 ↩︎

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kL_miBZmiy4 ↩︎

- Larry Dossey, The Trickster: Medicine’s forgotten character, Human Givens Institute, hgi.org.uk, https://www.hgi.org.uk/resources/delve-our-extensive-library/resources-and-techniques/trickster-medicines-forgotten ↩︎

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kL_miBZmiy4 ↩︎